A study published in 2022 revealed a tenuous but plausible link between picking your nose and increasing the risk of developing dementia.

In cases where picking at your nose damages internal tissues, critical species of bacteria have a clearer path to the brain, which responds to their presence in ways that resemble signs of Alzheimer's disease.

There are plenty of caveats here, not least that so far the supporting research is based on mice rather than humans, but the findings are definitely worth further investigation – and could improve our understanding of how Alzheimer's gets started, which remains something of a mystery.

A team of researchers led by scientists from Griffith University in Australia ran tests with a bacterium called Chlamydia pneumoniae, which can infect humans and cause pneumonia.

The bacteria has also been discovered in the majority of human brains affected by late-onset dementia.

It was demonstrated that in mice, the bacteria could travel up the olfactory nerve (joining the nasal cavity and the brain). What's more, when there was damage to the nasal epithelium (the thin tissue along the roof of the nasal cavity), nerve infections got worse.

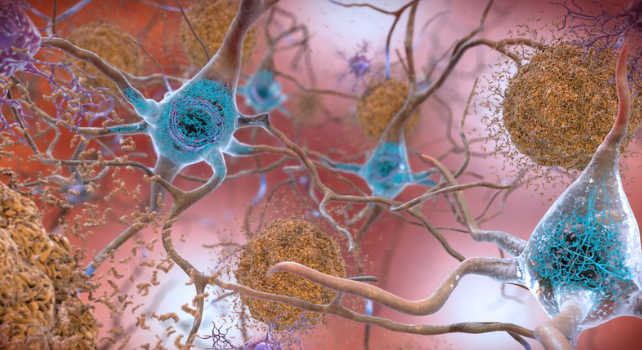

This led to the mouse brains depositing more of the amyloid-beta protein – a protein which is released in response to infections. Plaques (or clumps) of this protein are also found in significant concentrations in people with Alzheimer's disease.

"We're the first to show that Chlamydia pneumoniae can go directly up the nose and into the brain where it can set off pathologies that look like Alzheimer's disease," said neuroscientist James St John from Griffith University in Australia back in October 2022, when the study was released.

"We saw this happen in a mouse model, and the evidence is potentially scary for humans as well."

The scientists were surprised by the speed at which C. pneumoniae took hold in the central nervous system of the mice, with infection happening within 24 to 72 hours. It's thought that bacteria and viruses see the nose as a quick route to the brain.

While it's not certain that the effects will be the same in humans, or even that amyloid-beta plaques are a cause of Alzheimer's, it's nevertheless important to follow up promising leads in the fight to understand this common neurodegenerative condition.

"We need to do this study in humans and confirm whether the same pathway operates in the same way," said St John.

"It's research that has been proposed by many people, but not yet completed. What we do know is that these same bacteria are present in humans, but we haven't worked out how they get there."

Nose picking isn't exactly a rare thing. In fact, it's possible as many as 9 out of 10 people do it… not to mention a bunch of other species (some a little more adept than others). While the benefits aren't clear, studies like this one should give us pause before picking.

Future studies into the same processes in humans are planned – but until then, St John and his colleagues suggest that picking your nose and plucking your nose hair are "not a good idea" because of the potential damage it does to protective nose tissue.

One outstanding question that the team will be looking to answer is whether or not the increased amyloid-beta protein deposits are a natural, healthy immune response that can be reversed when the infection is fought off.

Alzheimer's is an incredibly complicated disease, as is clear from the sheer number of studies into it and the many different angles scientists are taking in trying to understand it – but each piece of research brings us a little bit closer to finding a way to stop it.

"Once you get over 65 years old, your risk factor goes right up, but we're looking at other causes as well, because it's not just age – it is environmental exposure as well," said St John.

"And we think that bacteria and viruses are critical."

The research was published in Scientific Reports.

A version of this article was first published in November 2022.