Case numbers of the infectious disease tularemia, also termed 'rabbit fever', have jumped in the United States over the past decade, according to a new report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

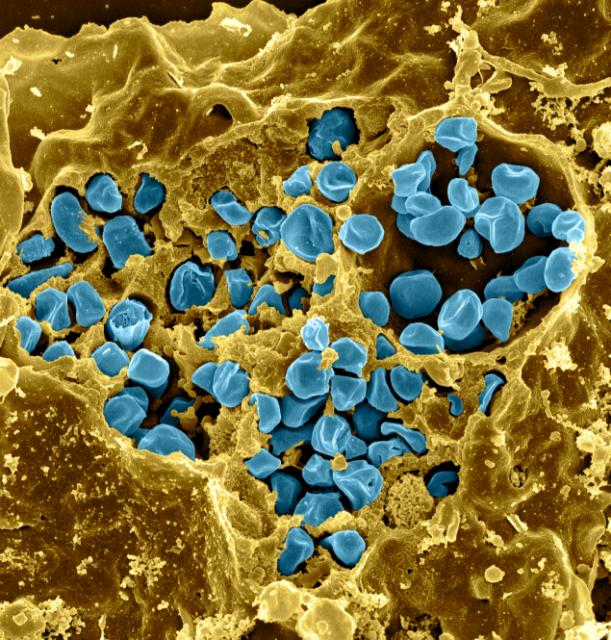

The disease, caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis, can be transmitted to humans in many ways, including bites from infected ticks and deer flies, and skin contact with infected rabbits, hares, and rodents, all of which are particularly susceptible to the disease.

But there are far gnarlier routes of transmission possible: lawn mowing over the nests of animals infected with the disease has been reported to aerosolize the bacteria, infecting the unwitting gardener.

This phenomenon was first recorded at a Massachusetts vineyard in 2000, where the resulting tularemia outbreak lasted six months and resulted in 15 identified cases and one reported death.

At least one of another handful of cases reported in Colorado in 2014 and 2015 was also linked to a lawn-mowing incident.

The CDC keeps a close eye on this bacterium, in part because it's classified as a Tier 1 Select Agent by the US government for its bioterrorism potential, and also because even when it's transmitted naturally, it can be lethal without treatment.

"The case fatality rate of tularemia is typically less than 2 percent but can be higher depending on clinical manifestation and infecting strain," the report's authors note.

Tularemia is relatively uncommon in the scheme of things: across 47 states, 2,462 cases were recorded for the decade 2011-2022. By comparison, the CDC estimates around 1.35 million cases of Salmonella bacterium poisoning occur across the country each year.

While those 2,462 tularemia cases amount to just one case among every 200,000 people, it's a 56 percent higher incidence rate than records from 2001-2010.

Some of this probably comes from improvements in the way we record cases: in 2017, the CDC began including cases where F. tularensis was detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to the 'probable case' count, which had previously included only cases where a person had symptoms, plus a few molecular markers hinting at the bacteria's presence.

Along with symptoms, for a case to be 'confirmed' a sample of the bacteria must be isolated from the infected person's body, or a massive change in related antibodies in serum testing will also suffice.

In the 2011-2022 data, there were 984 confirmed cases and 1,475 probable cases. That's 60 percent of the total cases classified as probable, a massive shift from the 2001-2010 data, where just 35 percent of cases were deemed probable.

"Increased reporting of probable cases might be associated with an actual increase in human infection, improved tularemia detection, or both," the CDC team writes. Commercially available laboratory tests also varied during this period, potentially impacting the data.

Incidence among the country's First Nations people, as defined by the CDC demographic category 'American Indian or Alaska Native', was around five times greater than among White people.

"Many factors might contribute to the higher risk for tularemia in this population, including the concentration of Native American reservations in central states and sociocultural or occupational activities that might increase contact with infected wildlife or arthropods," the report's authors write.

Others most affected by the disease were children aged five to nine years old, 65- to 84-year-old men, and people generally living in the central US.

It's difficult to diagnose tularemia because the symptoms vary greatly depending on mode of transmission. But better awareness about those routes of infection can help us avoid exposure and help doctors identify and treat the disease with antibiotics quickly.

For more detail, see the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.