A review on the health effects of microplastics has some scientists suspecting the worst.

The tiny synthetic particles that are found in our air, food, and water may be causing fertility issues, colon cancer, and poor lung function in humans, according to researchers at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF).

Picking out some of the strongest evidence on microplastics published between 2018 and 2024, the team has identified several health risks to the digestive, reproductive, and respiratory systems of animals.

Their work is not a full systematic review but a 'rapid' one, designed to identify possible health issues for urgent clinical research.

Of the 31 studies considered, most were conducted on rodents, and only three observational studies included humans. Current research on microplastics, however, is still in its infancy, and animal models are usually the first step.

The three human studies included in the review were conducted between 2022 and 2024, in Turkey, Iran, and China. One measured microplastics in maternal amniotic fluid, another measured them in placenta, and yet another in nasal fluid.

The animal experiments were mostly conducted on mice and at research institutions in China.

Scientists at UCSF say they are among the first to analyze the quality and strength of the existing health evidence on microplastics.

When it comes to sperm quality and health of the gut's immune response, the team rates the overall body of evidence as "high" quality.

Based on the results, the researchers conclude that microplastic exposure is "suspected" to have adverse impacts "based on consistent evidence" and "confidence in the association."

Evidence for respiratory issues, like lung injury, pulmonary function, or oxidative stress, was rated as "moderate" in quality, with microplastics also "suspected" of negatively impacting the lungs. Evidence for impact on egg follicles and other effects on the gut, such as chronic inflammation, was also deemed to be of moderate quality.

"Given the ubiquity of microplastics and the consistent, growing recognition of their existence in the human body, it is likely that microplastics will impact other body systems, which is a potential area for future research," the team predicts.

"This is particularly timely given that plastic production is projected to triple by 2060."

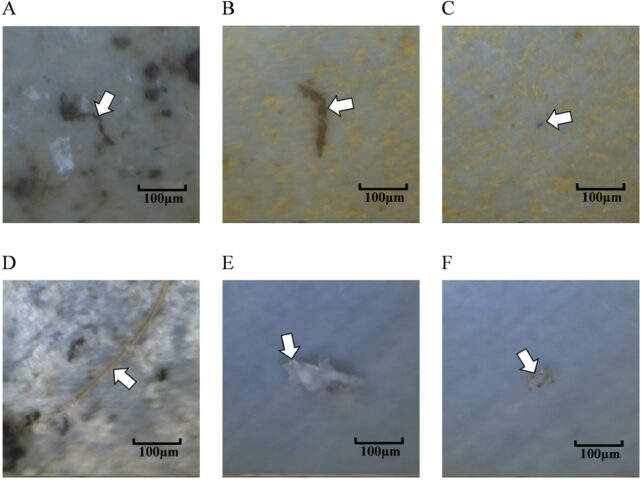

Today, fragments of plastic have been found accumulating in human placenta, poop, lung tissue, breastmilk, brain tissue, and blood with largely unknown consequences.

While many scientists around the world have warned microplastics may pose a risk to humans if they stick around in the body for long enough, plastic production continues to outpace health research by a long stretch.

No human study included in the review investigated digestion issues, but several animal studies revealed "significant alterations to the colon" following exposure to plastic, as well as a significant decrease in mucosal surface area that was commensurate with the animal's level of plastic exposure.

Five other animal studies also investigated changes to sperm. Microplastics were associated with declines in living sperm, sperm concentrations, and sperm movement, the researchers found. Increases in sperm malformation were also observed.

A further seven rodent studies assessed microplastic exposure and its links to chronic inflammation, lung injury, lung function, and oxidative stress. While the evidence here is not as strong as for fertility and digestive outcomes, experiments among animals consistently suggest damage and fibrosis to the lung tissue.

Given the state of the evidence, researchers at UCSF "strongly recommend" that regulatory agencies and decision makers "act on limited evidence given that evidence has been shown to grow and get stronger and initiate actions to prevent or mitigate human exposure to microplastics."

We don't have time to waste. Just a whole lot of plastic.

The study was published in Environmental Science & Technology.