The microbes living in our guts may have helped humans grow bigger brains. Lab experiments revealed that human gut microbiomes focus on energy production to feed our brains, rather than storage like in other animals.

"What happens in the gut may actually be the foundation that allowed our brains to develop over evolutionary time," Northwestern University anthropologist Katherine Amato told Gracie Abadee at BBC Science Focus.

Brain tissue is metabolically expensive, so our bodies would have needed to undergo a host of changes to cater for our larger thinking organs. The researchers were curious to see what role the helpful microbes living in our guts might have played in these transformations.

"We know the community of microbes living in the large intestine can produce compounds that affect aspects of human biology – for example, causing changes to metabolism that can lead to insulin resistance and weight gain," says Amato.

"Variation in the gut microbiota is an unexplored mechanism in which primate metabolism could facilitate different brain-energetic requirements."

Amato and colleagues seeded 'germ-free' mice with the microbiomes of three different primates to compare their impact. The mice received gut microbes from humans (Homo sapiens), squirrel monkeys (Saimiri boliviensis), and macaques (Macaca mulatta), and were then monitored with regular checks on weight, liver function, fat percentage, and fasting glucose.

Both humans and squirrel monkeys are classed as 'brain-prioritizing,' ending up with relatively large brains for their body sizes as adults. Macaques meanwhile have much smaller brains relative to their body size.

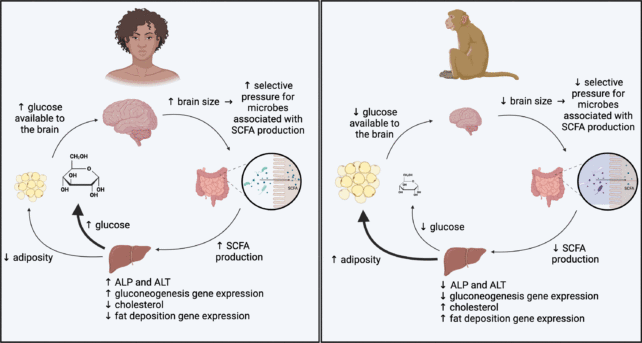

Mice inoculated with the human gut microbiome had the highest fasting glucose, highest triglyceride levels, lowest cholesterol levels, and also experienced the least weight gain. This suggests the human gut microbiome favors host production of brain-feeding sugar over storing energy in fats.

While these differences between the mice inoculated with the human microbiome and all the other primates were expected, the biggest differences were seen between the two big-brained species (humans and squirrel monkeys) and the small-brained macaques.

Despite only being distantly related to us, the squirrel monkeys have microbes that also shifted their host metabolism to prioritize energy use and production too, whereas those from the macaques promoted energy storage in fat tissue instead.

"These findings suggest that when humans and squirrel monkeys both separately evolved larger brains, their microbial communities changed in similar ways to help provide the necessary energy," explains Amato.

So developing and maintaining our expensive brain tissue may have required the help of our little gut symbiotes.

Previous research has shown there is a trade off between brain and body growth within and across mammals species. This is also seen during human development. Amato and team's new findings support this proposed trade off too.

"In humans, developmental changes in the brain's energy demands vary inversely with changes in growth rate between infancy and puberty, with the slowest pace of growth and fat deposition of the lifecycle coinciding with lifetime peak brain energy use in mid-childhood," the team write in their paper.

This research was published in Microbial Genomics.