Alternatives to cow's milk made from almonds, soy, oat, and rice have never been so popular. However, a new study suggests more research is needed into the nutritional trade-off that comes with plant-based milk substitutes.

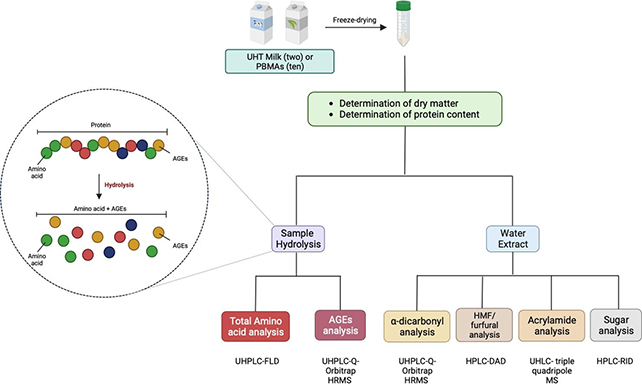

Researchers from the University of Brescia in Italy and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark examined the effects of Ultra High Temperature (UHT) treatments on the nutritional quality of 10 different plant-based milk alternatives (PBMAs), compared to two types of dairy milk.

UHT heats foods to temperatures above 140 °C (284 °F) to sterilize its contents and extend shelf life, but in many cases can also trigger chemical reactions that impact the food's nutritional value.

"Most plant-based drinks already have significantly less protein than cow's milk," says food scientist Marianne Nissen Lund from the University of Copenhagen. "And the protein, which is present in low content, is then additionally modified when heat treated."

"This leads to the loss of some essential amino acids, which are incredibly important for us. While the nutritional contents of plant-based drinks vary greatly, most of them have relatively low nutritional quality."

PBMAs undergo significant processing to turn the plant ingredients into something milk-like. The team looked for Maillard reaction products (MRPs), which are created as amino acids and various sugars are sufficiently heated.

MRPs can affect the nutritional value of proteins by reducing the availability of critical amino acids. While the mixes varied – soy milk had more protein than dairy milk, for example – the cow's milk had more protein than 8 out of 10 of the alternatives. What's more, amino acid counts were mostly higher in cow's milk.

Some PBMAs were found to contain concerning compounds, albeit in quantities that posed no danger. These chemicals included the carcinogen acrylamide, and the reactive substance hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF).

"We were surprised to find acrylamide because it isn't typically found in liquid food," says Lund. "One likely source is the roasted almonds used in one of the products."

Bear in mind that this all needs to be balanced with evidence of dairy milk's toll on the environment, or other health benefits, such as oat milk's protection against cancer. It's not a case of saying one type of milk is the best and all the others should be avoided.

However, the researchers do want to raise awareness of the potential nutritional shortfall in PBMAs, and perhaps to see more nutritional information on packaging. Their general advice is to focus on food and drinks that have had little processing applied to them, and to prepare as much of your own food as possible.

"Ideally, a green transition in the food sector shouldn't be characterized by taking plant ingredients, ultra-process them, and then assuming a healthy outcome," says Lund.

"Even though these products are neither dangerous nor explicitly unhealthy, they are often not particularly nutritious for us either."

The research has been published in Food Research International.