One of the main viruses responsible for seasonal flu may remain infectious in raw milk days after it has left a warm body, according to new experiments at Stanford University, raising concerns about the potential spread of avian influenza or 'bird flu'.

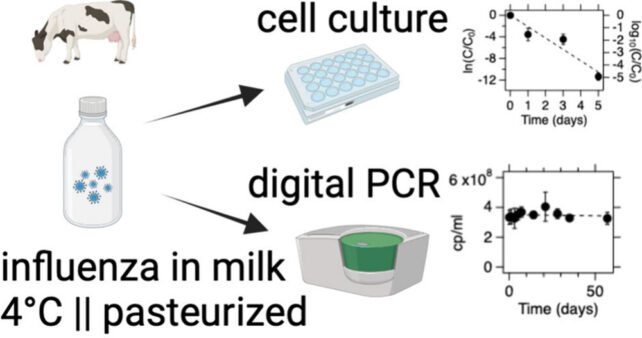

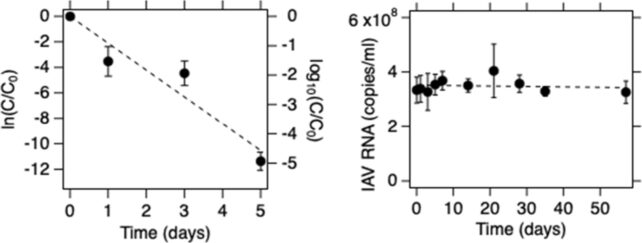

When researchers infected a batch of raw milk with the H1N1 virus – a subtype of the influenza A virus – and kept it at a relatively standard domestic refrigeration temperature of 4 °C (about 39 °F), they found it took the pathogen 2.3 days to reach a 99 percent reduction in infectivity.

Alarmingly, a small fraction of the virus particles remained in a transmissable state for up to five days. The recommended shelf life of refrigerated raw milk is between five and seven days, meaning even under ideal circumstances milk containing the virus could transmit the flu to a consumer.

Thankfully, pasteurization resolved the threat. When researchers heated infected milk to 63 °C for 30 minutes, they successfully inactivated the infectious influenza A virus.

"This work highlights the potential risk of avian influenza transmission through consumption of raw milk and the importance of milk pasteurization," says environmental engineer Alexandria Boehm from Stanford.

Boehm and her colleagues say they could find no other study that has investigated how long viruses can remain infective in raw milk. Theirs is the first, and it comes at a critical time.

In a world first, an outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in the US has officially made the jump from birds to cows, infecting hundreds of dairy farms across the nation with the H5N1 virus.

The H1N1 virus is often used as a surrogate for the H5N1 virus in research, so these results from Stanford confirm the idea that pasteurization protects the public against flu-infected milk.

While this particular strain of bird flu has yet to be observed spreading from human to human, it can jump from animal to human, and initial research suggests cow milk is a possible vector for human infection.

Just a few weeks ago, public health officials in California detected the H5N1 virus in raw milk that was being sold. All of the products were recalled for fear they would infect consumers.

At this point, it seems the H5N1 virus can infiltrate a cow's mammary glands and infect dairy farm workers who handle raw milk or milking machines. Some domesticated cats on dairy farms have even died from drinking raw, infected milk.

"The persistence of influenza viruses in raw milk is concerning, as the consumption of raw milk remains high in the United States due to cultural factors and several popular misconceptions," the authors write.

"Some of these misconceptions include beliefs that raw milk could cure lactose intolerance or asthma, enhance the immune system, and have greater nutritional value compared to pasteurized milk."

None of these arguments are ultimately backed up by evidence, and the risks from drinking raw milk can be extremely dangerous, even fatal.

About 4 percent of Americans drink raw milk at least once each year, but even with such a small population directly exposed to the risk, there is a threat to public health. The more time the HPAI virus spends in a human body, the more chances it has to get to know the terrain, possibly mutating to better infect our species down the road.

So far, US dairy farm workers that have fallen ill have experienced only mild symptoms, but historically, H5N1 outbreaks among humans have high fatality rates, sitting somewhere around 50 percent.

Even without bird flu on the scene, health officials warn that drinking unpasteurized milk can expose consumers to pathogens, such as Listeria, Salmonella, Campylobacter, and E. coli.

Today, this health advice is more important than ever.

The study was published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.