Blood vessels at the back of your eye may one day alert doctors to signs of early dementia, a new study suggests.

Multiple studies have found links between eye problems and dementia risk. Plaques of amyloid beta proteins, a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease, have even been found in the retinas of people who have it.

Three years ago, researchers from the University of Otago in New Zealand discovered that thinning in a person's retina in middle age can be linked to cognitive performance in their early and adult life. That's the light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye.

The scientists suspected these findings could one day pave the way towards a simple eye test to help predict a person's risk for conditions such as Alzheimer's disease. Now, some members of that team have followed the hunch a step further.

"In our study, we looked at the retina, which is directly connected to the brain," University of Otago psychologist Ashleigh Barrett-Young says.

"It's thought that many of the disease processes in Alzheimer's are reflected in the retina, making it a good target as a biomarker to identify people at risk of developing dementia."

Barrett-Young and colleagues returned to the longitudinal database used in their 2022 research, the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, which tracked 45 years of health data from New Zealanders born in 1972 and 1973.

For their new research, the team only used data collected from 938 participants at age 45, including retinal photographs, eye scans, and a battery of tests that gauge midlife risk of Alzheimer's and related dementias.

Repeating the major part of their 2022 study, they checked for associations between cognitive decline and retinal layer thickness.

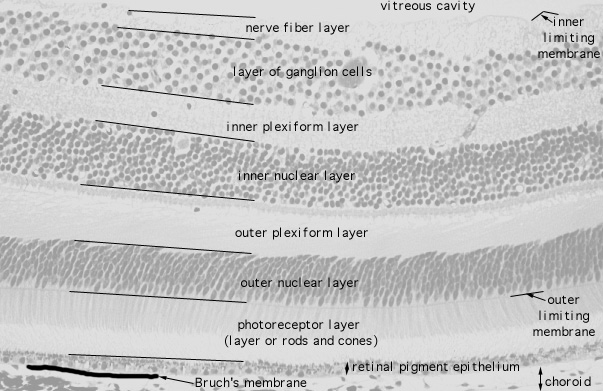

They took special care over the layer of nerve fibers closest to the jelly-filled vitreous cavity that 'fills out' our rounded eyes, and its neighboring layers of ganglion cells and inner plexiform. The nerve fiber layer is particularly important because it carries visual signals to the brain.

They also looked for possible associations with retinal microvascular health, ascertained by measuring the diameter of tiny arteries and veins in the retina. These "are believed to reflect the integrity of the overall cardiovascular system of the body (including the cerebrovasculature), which is implicated in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias and, in particular, vascular dementias," the team writes.

It turns out that, at least for the 45-year-old Kiwis involved in the study, retinal microvascular health was a much stronger predictor of dementia risk than the nerve fiber layer.

While thickness of the nerve fiber layer (though not the ganglion cell–inner plexiform layer) was weakly associated with dementia risk, it was nowhere near as strong as the microvascular link.

The team found dementia risk scores were usually higher among people with narrower arterioles (tiny vessels that carry blood away from the heart) and wider venules (miniature veins that receive blood from capillaries).

Medical professionals won't be putting the findings of this study into action just yet, because it's too population-specific and observational. Also, as the authors note, while the dementia risk measures are "highly predictive of the likelihood of dementia decades later", they are by no means a direct measure of actual disease.

Nonetheless, it seems we're getting closer to a world where a routine eye check could help flag the risk of dementia before it hits, and give you more time to plan treatment.

"Treatments for Alzheimer's and some other forms of dementia may be most effective if they're started early in the disease course," Barrett-Young says.

"Hopefully, one day we'll be able to use AI methods on eye scans to give you an indication of your brain health, but we're not there yet."

The research was published in Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.