New hope for earlier treatment might be on the horizon for people suffering the most severe form of depression.

In a study of patients watching emotionally evocative movies, the responses of people with a form of depression known as melancholia were distinctly different from those of patients with a less severe form of the depression.

This discovery could lead to a diagnosis of melancholia sooner, helping patients get the right treatment quickly to avoid the more invasive interventions that might be required if the diagnosis is delayed.

"For basically as long as depression has been recognized as a condition, as far back as the times of the ancient Greeks, it's been noted that there are some people with depression that seem to get a very physical presentation," neuropsychiatrist Philip Mosley of QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Australia told ScienceAlert.

"So they stop eating, they lose the ability to sleep, they seem slowed down as if they're walking through concrete. Their speed of thought reduces markedly, and they are often very sick."

Called melancholia, this sub-type of depression often fails to respond well to psychological treatments. Mosley describes the research as an effort to create a toolbox that allows specialists to diagnose types of depression with a degree of precision that permits a prompt, tailored approach.

Melancholia affects around five to 10 percent of all people with depression, and it can often be challenging to diagnose. The later it is diagnosed, the more likely it is the patient may need a stronger treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy or transcranial magnetic stimulation. These treatments are very effective, but also can feel intimidating and invasive.

For early diagnoses, medication can be quite effective, and that is what Mosley and his colleagues are trying to achieve.

Other studies at QIMR Berghofer involve the use of emotional videos to study the responses of people with various neurological and psychological conditions. Since one of the manifestations of melancholic depression is a flat affect, Mosley wanted to investigate whether the condition could be gauged by observing emotional responses, or lack thereof, in depressive patients.

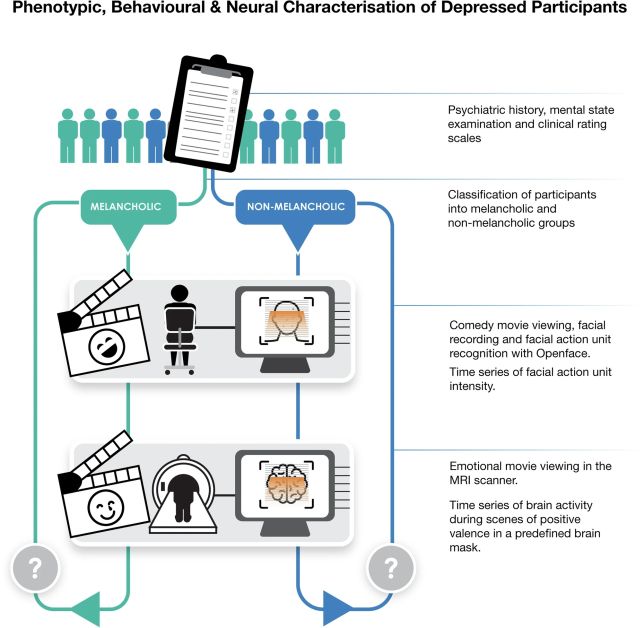

Their study involved 70 patients with depression: 30 with melancholic depression and 40 with non-melancholic depression. These patients were shown two videos, a funny video of a comedian's set carefully edited to remove offensive material (Ricky Gervais' Animals, for the curious), and a short film about a traveling circus called The Butterfly Circus that, Mosley said, is "quite moving" and elicits a lot of brain activity.

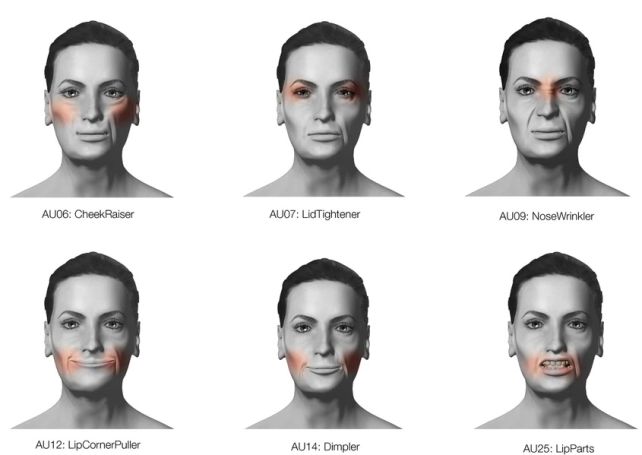

While the patients watched the videos, their facial and brain activity was recorded, the former with a camera to track every minute muscle twitch during the Gervais set, the latter with the patient in an MRI machine while watching The Butterfly Circus.

The difference between the two patient sets was stark. For the Gervais video, although the patients with non-melancholic depression were still depressed, they did respond with facial expressions and giggles. Meanwhile, the patients with melancholic depression were completely impassive. Mosley describes them like "statues" with "no facial movement at all, no smiling, no chuckling."

Something similar happened in the MRI machine. The brains of patients with non-melancholic depression lit up, particularly in the cerebellum, which is involved with automatic emotional responses.

"With people with melancholic depression," Mosley said, "those emotional regions of the brain – the ones involved in detecting and responding to stimuli with an emotional tone – were just doing their own thing, disconnected, not integrated with the rest of the brain, not involved in processing with other regions of the brain that are relevant in these tasks."

This clear difference between the two levels of response could be an extremely useful diagnostic tool that can be performed quickly and non-invasively, without needing to wait months to see a psychiatrist. Instead, those precious months could be used obtaining the right treatment for the kind of depression the patient suffers.

But this research could have longer term implications. We don't know why some people get depression, and why that depression can occasionally be severe enough to be life-threatening. Learning about the differences between the forms depression can take on a mechanistic level can ultimately help direct the right treatment to everyone who suffers from it.

"In this study, we've shown that melancholia, which has long been considered a separate type of depression right back through literary times and even even the ancient Greeks wrote about it, really does differ in terms of the brain and physical manifestations of depression," Mosley said, "which then leads us to think, well, maybe we should be approaching this in a different way to get people better quicker."

The team's findings have been published in Molecular Psychiatry.

If you think you may have melancholic depression, the best option for diagnosis is still currently a psychiatrist. Please talk to your doctor about seeking an appointment.

If this story has raised concerns or you need to talk to someone, please consult this list to find a 24/7 crisis hotline in your country, and reach out for help.

If you wish to participate in the Genetics of Depression study currently underway at QIMR Berghofer in Australia, you can find contact details on its website.